Esbjerg has become the first wind port in the world to commission a so-called digital twin that can calculate efficient methods for deploying offshore wind installations. The effect of the calculations is dramatic: The port can triple its annual shipping capacity for offshore wind installations from 1.5 GW to 4.5 GW within three years. “These are big numbers. This means that we can increase the pace of the green transition because we use the space we have more efficiently,” says Port Esbjerg CEO Dennis Jul Pedersen.

How much space does a turbine blade actually require when it is stored at the port? How much space is needed for eighty blades? Or eighty nacelles?

And where should they be stored at the port to ensure the most time-efficient loading of the installation vessel?

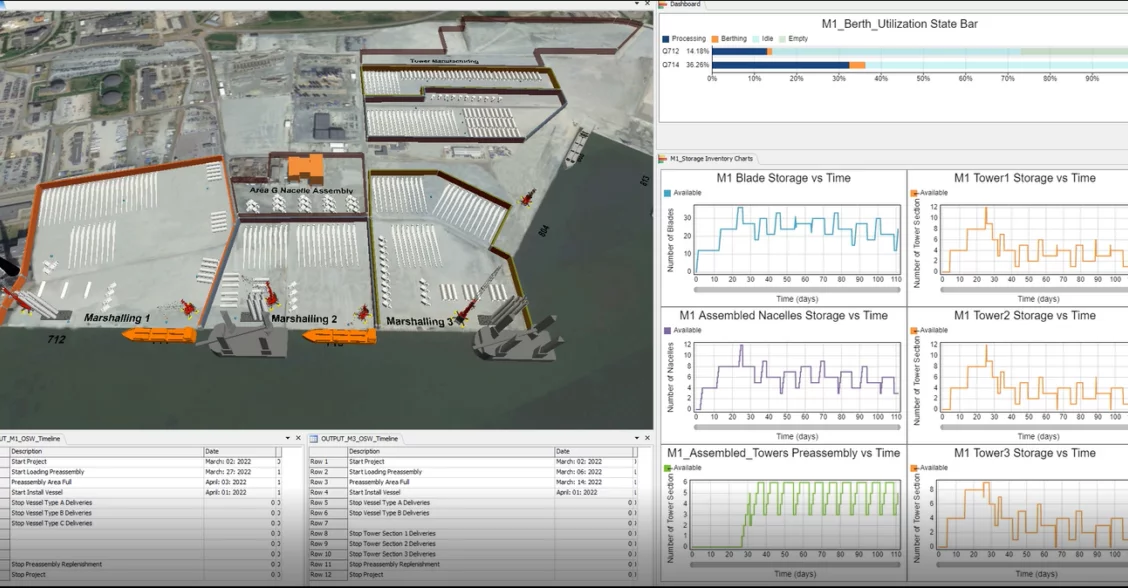

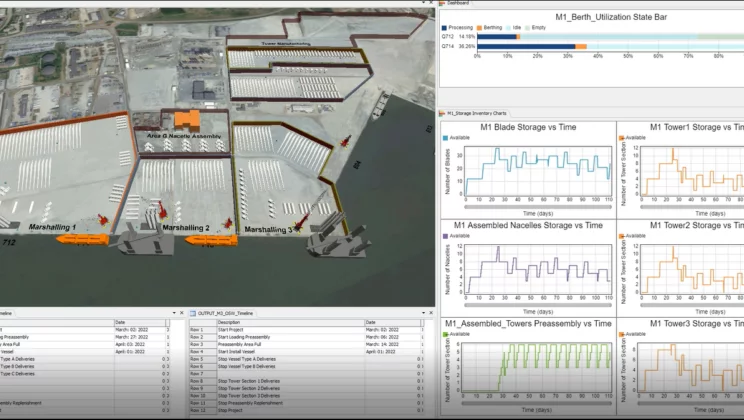

The employees at the port will no longer have to spend time working that out, because a so-called digital twin of the port has calculated this down to the smallest detail.

“We’ve already simulated everything down to the smallest detail,” as Jul Pedersen puts it.

In addition to optimising the use of space at the port, the digital tool has also established optimal locations for storing wind turbine components and calculated that a deeper basin is needed in a few places, a few extra access routes and other practical solutions. All of this will help ensure that in three years’ time, Port Esbjerg will be able to ship 4.5 GW of offshore wind capacity in a year. This is a threefold increase compared to the 1.5 GW that has been possible until now.

“It may sound strange, but we’re not actually surprised by the results. Working with a digital twin is relatively new in port operations, but we’ve seen such great results already in RoRo and container cargo that we expected something similar when we started this project,” Jul Pedersen explains.

In the past, a digital twin helped Port Esbjerg achieve improvements in the RoRo traffic.

The digital twin is a dynamic, virtual representation of the port, updated from real time data and using simulation, machine learning and reasoning to help decision making at Port Esbjerg.

From guesswork to artificial intelligence

The digital twin is a computer program, which is fed vast amounts of data on everything from upland storage space and berth characteristics to the port’s experience with shipping offshore wind installations gathered over the past twenty years. Then, the program runs modelling simulations with variables on everything from on and offloading times to weather induced down times.

Before the digital twin was developed, booking a project typically involved an educated guess at space requirements. The smartest location of cargo in relation to ships was not worked out in detail.

In the future, all that will be worked out carefully.

“Twenty seconds saved here and there all adds up. A project like this is made up of many such actions,” says Jul Pedersen.

When shipping and staging offshore wind components, the optimal design of the process at the port is extra important, because it can be more complex than other port processes. Many activities are going on at the same time. For example, different ships come from different countries bringing specialist equipment. This adds extra pieces to an already complicated puzzle and it is costly to make mistakes. Installation ships cost upwards of USD 300,000 a day.

Improving the port’s competitiveness

Tripling its capacity gives Port Esbjerg a competitive edge.

“Efficiency is a competitive parameter. On account of the digital twin, we’re already booking in many more projects for the coming period, because we’ll have room for more,” says Jul Pedersen.

He makes the point that they have experienced overbooking space at the port for one project, while turning down another due to lack of space.

“It’s tremendously frustrating. And we’ve also experienced the opposite: that we didn’t have enough space for a project that was already booked in. However, with the digital twin, problems like these are a thing of the past,” says Jul Pedersen.

Capacity shortage during the green transition

One of the main challenges of the green transition is capacity problems, not least at wind ports in Europe. With the Esbjerg Declaration of 2022, it was agreed to deliver at least 65 GW offshore wind by 2030 and at least 150 GW by 2050. To achieve these targets, the pace of deploying offshore wind installations must be stepped up significantly.

“Working with a digital twin is a gamechanger. We’re able to make much better decisions using that tool. When it comes to port capacity and offshore wind, we need to pull the ports out of our spreadsheets and create more digital twins instead,” says Jul Pedersen.

The capacity at Esbjerg will steadily increase from 1.5 GW to 4.5 GW by 2025, when the required changes will have been completed.

“And it’s one thing what we can implement as a port. Just think what we can achieve when we get suppliers and other ports entered into our digital twin. With nacelles from Cuxhaven and blades from Hull,” says Jul Pedersen.

He is therefore particularly looking forward to meeting with representatives of the other major wind ports in Esbjerg on 18 January, when he will share Port Esbjerg’s preliminary experiences of using the digital twin.

“After all, the potential is enormous. If all wind ports did what we’re doing, the rest of Europe already in the short term can more than triple the capacity without expanding the ports by a single square meter,” says Jul Pedersen.

By using the digital twin, the port can triple its annual shipping capacity for offshore wind installations from 1.5 GW to 4.5 GW within three years.

The world’s premier ports & maritime engineering consultancy company created Esbjerg’s digital twin

The US company Moffatt & Nichol developed the digital twin for Port Esbjerg. It is the world’s premier ports & maritime engineering consultancy, entrusted with planning and designing ports all over the world. They have a division dedicated to the planning, logistics modelling and detailed design of ports to support the offshore wind industry in Europe and the US.

“Developing the digital twin was challenging and required significant effort, however it has proven to be a very rewarding and worthwhile exercise. The ability to digitally build out the port and physically see the project happening and identify issues and efficiencies prior to significant capital expenditure provides a tremendously powerful tool for the offshore wind port industry. We can run what-if scenarios and optimize a port to ensure an efficient operation and maximum throughput,” says Joshua Singer.

Singer is an offshore wind port planner and marine structural engineer with twenty-two years of experience, who has been working with wind installations for the past eight years, and he was the project manager on the development of the digital twin.

According to Singer, it was no coincidence that Esbjerg became the first port in the world to have a digital twin to calculate the port processes in deploying offshore wind components.

“We also work with wind ports in the United States, but Esbjerg’s Dennis Jul Pedersen saw the possibilities and he pushed for it. Then we met, and Esbjerg is a giant in the field, so we decided to collaborate to make the world’s first model for deploying wind installations,” says Singer.

He explains that the application is a dynamic simulation model of the port, used to test the processes taking place at Esbjerg. How is a turbine blade moved? It is tested in many different ways to ensure that all the processes are made as smart as possible. The simulations also allow for RoRo and onshore wind, container and bulk projects that take place at the port at the same time. The helps ensure that other existing port operations are not downgraded due to increased offshore wind activities. The program must also take into account that wind turbine components need to be close to the sea, wind terminals must be close to each other and need to be adjustable up and down in size.

As wind farm components are increasing in size, the need for careful planning becomes even greater.

“Esbjerg was good at optimising before, but the entire logistics chain is challenged by the giant components of offshore wind. As the components grow in size, the land based supply chains will shrink and the vast majority of components will be transported on the water. How do we coordinate so the timing is optimal for cranes, ships and so on? What if we move this vessel over here, then what? Well, that didn’t work. It’s a huge puzzle, and if you’re trying to work it out on a piece of paper or in Excel, you just can’t wrap your head around it,” says Singer.

"It’s a great achievement that we’ve accomplished together, and one that we can definitely use here in the United States and elsewhere in Europe,” says Joshua Singer, project manager on the development of the digital twin.

Great achievement

Moffatt & Nichol has also developed digital twins for other port processes, such as container transport. A digital twin is certainly always a help, but container processes have been well studied over many years. By contrast, the wind industry is much younger, so the improvements achieved are more significant.

“All credit to Esbjerg and Dennis Jul Pedersen. I’ve got to admit that working with the largest wind port in the world was a little scary at first. But it’s a great achievement that we’ve accomplished together, and one that we can definitely use here in the United States and elsewhere in Europe,” says Singer.

Singer explains that the digital twin allows Port Esbjerg to simulate any operation relevant to future projects and to optimise the infrastructure accordingly.

Jul Pedersen is equally delighted that Moffatt & Nichol chose to work with Port Esbjerg on this important project.

“It’s the world’s first digital twin for offshore wind processes. Moffatt & Nichol could have chosen to work with anyone on this project, but they chose us. It also speaks volumes about the international standing of Port Esbjerg,” he says.

Go to overview