Wind turbine decommissioning is expected to become a booming market in the coming years. At Port Esbjerg, 100,000 sq.m. have already been allocated to the handling of used turbine components, as Europe's 105,000 wind turbines are dismantled. Nacelles and towers can be reused, while blades pose a challenge.

When onshore and offshore wind turbines are to be replaced or dismantled completely because they are no longer profitable or their technology is outdated, the owners are left with some enormous turbine components. What do you do with a stack of 39-metre blades or a pile of towers exceeding 100 metres, not to mention all the electronics in the turbines?

This is an ever more urgent issue for the wind industry. During the next five years, it is expected that a European offshore wind farm will be decommissioned virtually every year. This figure is also set to rise, since in 2028, five wind farms are expected to be decommissioned - and in 2038 the number will have risen to 12. These are the figures reported by the Dutch company Virol which specialises in recycling materials.

At Port Esbjerg too, decommissioning has become an increasingly important element of the port’s future plans. CEO Dennis Jul Pedersen expects that low electricity prices and current wind turbine trends will speed up the development of this market:

“The size of the turbines is growing rapidly at the moment. This means that small turbines quickly become less profitable when subsidies are no longer provided and electricity prices are low. Even though the wind farms have a technical lifetime of 20-25 years, I expect the market’s impatience to speed up the decommissioning rate.”

Semco Maritime, headquartered in Port Esbjerg, is monitoring this development closely:

“Right now, we’re keeping a close eye on the market and on how the decommissioning tasks are structured. We can see opportunities for a lot of onshore jobs with regard to the planning and the development of new solutions and also for offshore jobs within lifting and transport operations,” says Lars Christensen, Senior Vice President at Semco Maritime.

The first offshore wind farms have already been decommissioned. In 2016, Vattenfall dismantled the Swedish Yttre Stengrund offshore wind farm, followed one year later by Orsted’s Vindeby farm off the coast of Lolland, Denmark. In the same year, speculation began about the fate of the 80 turbines at the Danish wind farm Horns Rev 1, which will celebrate its 20th birthday in 2022.

Port Esbjerg is following the debate closely:

“When it comes to Horns Rev 1, which is located just outside Esbjerg, we’ll obviously have a role to play,” says Dennis Jul Pedersen.

Right now, 50,000 of Europe’s 105,000 wind turbines are more than ten years old. This presents good opportunities in the decommissioning market.

Port Esbjerg commands a strong position

However, the potential decommissioning market extends beyond Horns Rev 1, since right now there are 105,000 wind turbines in Europe alone, of which 50,000 are more than ten years old and will need to be replaced or removed within the foreseeable future. Virol estimates that in 2030 there will be around 150,000 MT of turbine waste in Europe and on this basis foresees great opportunities for Port Esbjerg.

“Port Esbjerg has a prime location and also has a major role to play, especially when it comes to offshore wind turbines. They already have considerable expertise in handling large turbine components. This will be a great advantage when it comes to playing a role in the future market,” says Nina Vielen-Kallio, New Business Manager at Virol.

According to Lars Christensen from Semco Maritime, another prerequisite for gaining a foothold in the market is the ability to develop new, multidisciplinary solutions, especially when it comes to lifting, dismantling and transporting the redundant turbine components. He is convinced that the decommissioning of wind turbines will bring operators together who have not previously cooperated.

“At Semco Maritime, we’re working hard to find the right partnerships. We have, for example, established a consortium with Stena Recycling here in Esbjerg, so that we can offer holistic solutions once the wind decommissioning assignments start coming in,” says Lars Christensen.

What happens to the turbines?

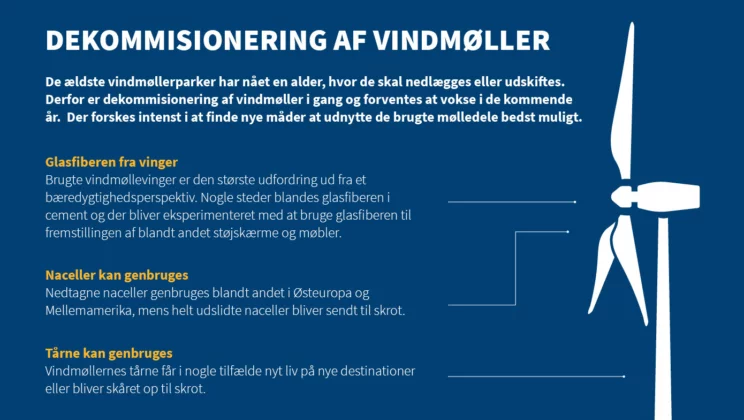

When wind farms are dismantled, some nacelles and towers can be reused in other wind farms, while the large volumes of fibreglass from the wind turbine blades constitute a challenge from a sustainability perspective.

According to Nina Vielen-Kallio from Virol, in the overall scheme of things the most sustainable solution right now is to cut the blades into tiny pieces and mix them into cement. Virol has also launched a pilot project to investigate the possibility of using pyrolysis to convert the blades into valuable chemicals, which can be further used to make new products.

She also describes other, small-scale solutions. For example, the Danish company Miljøskærm uses fibreglass from blades to producecoustic barriers, and a Dutch company mixes fibreglass with plastic to manufacture furniture.

Regardless whether the blades are transformed into cement or acoustic barriers, they still need to be transported. As the transportation of the long blades is very expensive, the blades are usually cut into smaller pieces so that they do not require special transport measures.

This process forms part of the basis for Port Esbjerg’s decision to allocate 100,000 sq.m. for decommissioning activities. The area will, however, also be used for the storage of used turbines before they are shipped out.

“A lot of turbines can be used in other markets, and it’s great that they can be part of the green transition in this way,” says Dennis Jul Pedersen.

Also about responsibility

Decommissioning of both onshore and offshore wind turbines is of interest to Port Esbjerg. In fact, Dennis Jul Pedersen believes that, in view of the port' leading position within wind installation, Port Esbjerg should also be involved in securing that the dismantling of the turbines is carried out in a proper way.

“I think that decommissioning will become a major business area in the course of the next five years and we need to play an active role in this. Port Esbjerg wants to be an active player in the circular economy,” says Dennis Jul Pedersen.

Lars Christensen of Semco Maritime also recognizes the responsibility:

“As we in Denmark were among the first to install wind farms, we should also be the first to take them down again,” he says.

Go to overview