The building called ‘Det Gule Palæ’ on the harbour front at Esbjerg has been renovated inside and out to become a visitor centre. It will welcome the thousands of visitors who visit the port of Esbjerg every year, providing an insight into the origins of the port and the history of Esbjerg. In addition, there are lots of weird and wonderful anecdotes from the time the harbour was built and right until it became the workplace of 10,000 people. Read on to learn about some of these anecdotes.

“We could have filled our local stadium, Blue Water Dokken, if they’d let us include all the anecdotes and historical artefacts that we would have liked,” explains Jørgen Dieckmann Rasmussen with a wry smile, just noticeable behind the blue mask which he is wearing – like the rest of us – to keep us all safe in these challenging times.

He is the head of Esbjerg City Archives and one of the people who is most knowledgeable about the history of the port. We meet him at the Archives, standing in front of a table on which there is an old map of the harbour facilities, old negatives of photographs, historical books and a hand-coloured postcard of the harbour in Esbjerg with a 1920 postmark. At the centre of the map, there is a building which is now called Det Gule Palæ.

The reason for our visit is that Port Esbjerg has renovated and opened Det Gule Palæ: the port’s new visitor centre, inaugurated by Esbjerg’s mayor, Jesper Frost Rasmussen, on 16 September this year.

The visitor centre will serve as the meeting point for visits, walks and the 250 bus tours that take place on the harbour every year. The centre provides visitors with a sense of the origins of the port, from which Esbjerg grew, in an exhibition of historical photos blown up on posters, texts and historical artefacts supplied by the Fisheries and Maritime Museum and Esbjerg City Archives, predominantly from the time around 1910.

Visitors will also notice the ox hanging from the ceiling. It is a nod to the export of live cattle to Britain in times gone by. A map of the dock anno 1910 is another interesting exhibit, as are the many historical photos from the harbour, among them one stands out depicting one of the very oldest ferries used on the route to Britain.

Det Gule Palæ at Port Esbjerg has been renovated and is now a visitor centre that will serve as the meeting point for visits, walks and the 250 bus tours that take place on the harbour every year. Photo: Port Esbjerg.

Big flashy car hoisted on board

However, the exhibition in Det Gule Palæ includes only a small section of the port’s overall history. There is also an incredible wealth of good anecdotes, and the head and the clerk of Esbjerg City Archives, Jørgen Dieckmann Rasmussen and Lars Hyldahl Brockhoff, who created the exhibition, have lots of these to share.

Brockhoff holds up against the light some of the negatives that were lying on the table at Esbjerg City Archives. The negatives are from 1952 and they are photographs taken by the then press photographer, Knud Rasmussen, who was employed by the Vestkysten newspaper.

“At the time, everyone who was going to Britain or via Britain into the wider world had to sail from Esbjerg. The entertainer Victor Borge, for instance, was a frequent passenger, and the photographs show the Copenhagen milk delivery boy Carl Brisson who lived the American Dream and became an actor in the USA. He was in Esbjerg with his Isotta Franchini that was coming with him on board the ferry. Back then, cars did not drive on board. They were goods that was hoisted on board – in fact, that was the case until the mid-1960s,” explains Dieckmann Rasmussen.

He shows us a large, brown photo album which also holds a large number of photographs of the harbour dated at the beginning of the 1900s. A special feature of Denmark’s youngest city is that it started to grow at the same time as photography began to come into its own in Denmark, which is undoubtedly why the origins of both the harbour and Esbjerg are so well documented. Many of the photographs are on view at Det Gule Palæ, but unfortunately many more have had to stay in storage due to shortage of space.

Lots left out

The hearts of the two historians at Esbjerg City Archives bleed at the shortage of space at Det Gule Palæ, which has meant that many worthy anecdotes and historical documents have not been included in the exhibition.

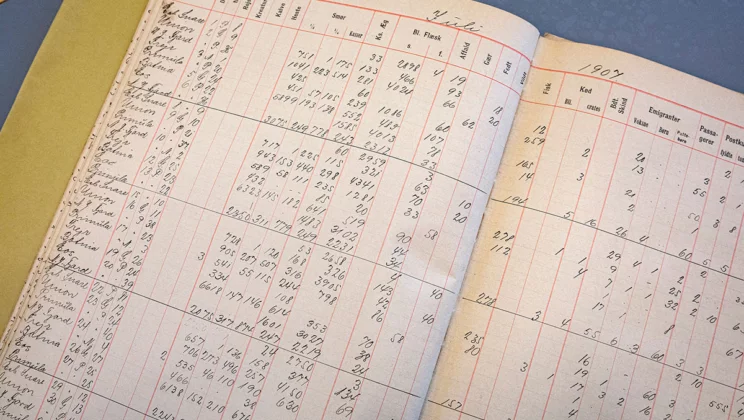

Brockhoff is especially sad that there was not space for one particular register. When he opens it, you see page after page of columns completed in the most beautiful handwriting. The register, dating from 1907, was kept by DFDS and contains detailed records of the ships and goods that left the harbour – anything from cattle and fat to eggs, yeast and emigrants.

“At the time, many ships carried more emigrants than ordinary passengers,” explains Brockhoff.

It takes some effort to decipher the register, written more than a century ago, which was indeed the reason why it was decided not to include it in the exhibition, just like many other historical documents – not least the weirdest of anecdotes. For example, the story about all the different nicknames given to people at the harbour was also left out of the exhibition at Det Gule Palæ. The disappointment in Dieckmann Rasmussen’s voice is only too noticeable.

“Nobody working on the harbour was referred to by their real name at the beginning of the 1900s. There’s an anecdote about a young man who turned up to bring his father-in-law, Kristian Hansen, a packed lunch. However, when he asked for him, he was told that there was nobody by that name at the harbour. Finally, somebody twigged that he was looking for ‘Kristian with the dead sow’. The fact was that there were two Kristians and you had to differentiate between them in one way or another, and obviously one of them had a sow at some point that died,” explains Dieckmann Rasmussen with a wide grin.

The register, dating from 1907, was kept by DFDS and contains detailed records of the ships and goods that left the harbour – anything from cattle and fat to eggs, yeast and emigrants. Photo: Port Esbjerg.

From architect-designed storehouse to visitor centre

Four kilometres away from the historical documents, standing among shelves upon shelves of old scales, foghorns, fish nets, pots from the 1600s recovered from the sea, weighing buckets, lanterns and name boards from fishing vessels, we find Richard Bøllund. He is the curator of the Fisheries and Maritime Museum and has also contributed to creating the exhibition at Det Gule Palæ. We are in the museum’s storeroom which has a distinct smell of tar, surrounded by history and anecdotes of the harbour when fishing was at the heart of the activities there.

“Fishing wasn’t even planned when the harbour was built, but the fishermen along the west coast soon noticed Esbjerg and seemed to favour it, and when the industry was at its peak during the 1970s, there were more than 600 fishing vessels at Esbjerg,” says Bøllund.

However, back in 1868, when the act on building a port at Esbjerg was passed, nobody gave much thought to fishing. It was mainly built to facilitate the export of cattle to Britain, and Det Gule Palæ was to play its own part in this important industry.

“Det Gule Palæ was designed by the architect C. H. Clausen who also designed Esbjerg’s Water Tower. Det Gule Palæ was to be the ‘port storehouse’ as it says in the original drawings, but the building also served as a quarantine cattle shed,” explains Bøllund.

In 1922, more than 10,000 cattle were exported out of Esbjerg, which is also why there is a stuffed ox hanging from the ceiling in Det Gule Palæ, an exhibit provided by the Fisheries and Maritime Museum. One might say that it symbolises the birth of Esbjerg in 1868. The sling used to suspend the animal also comes from the museum.

“It is an original sling used to hoist cattle on board ships. The one on show here is of a more recent date, around 1940–1960,” explains Bøllund.

In 1922, more than 10,000 cattle were exported out of Esbjerg, which is also why there is a stuffed ox hanging from the ceiling in Det Gule Palæ, an exhibit provided by the Fisheries and Maritime Museum. Photo: Port Esbjerg.

Esbjerg’s largest playground

We walk around the museum and stop in front of a large, black wooden box filled with holes in the base and sides and with no lid. It is a so-called well-box in which the fishermen stored caught, live fish, so they would keep longer. The well-box is one of the exhibits which Bøllund would have been pleased to see in the exhibition at Det Gule Palæ, because it testifies to a golden age when the harbour was the heart of Esbjerg and the children’s playground.

“The well-boxes sat side by side, and the children jumped from one to the other, playing tag. Their mums weren’t too happy about it, but they accepted it anyway, as the children would sometimes return home with fresh fish, the gifts from a kind fisherman. At the time, the harbour was Esbjerg’s largest playground, as it was always a hive of activity – as late as the 1950s to 1970s when the fishing industry reached its peak,” explains Bøllund.

The port of Esbjerg was also a hub for the onward travel into the wider world. Thus, the quay was often filled with local residents, waving goodbye to royalty and other celebrities, embarking on – usually – major journeys.

These days, the harbour is a very different place of work, which is far less accessible. Instead, visitors are now invited to get a sense of the life at the harbour in the early 1900s by exploring the newly opened visitor centre. Det Gule Palæ opened on 16 September, observing appropriate Covid-19 restrictions, and in the longer term, the plan is to put on various Open House events, lectures and changing exhibitions.

The well-boxes sat side by side, and the children jumped from one to the other, playing tag. This original well-box is exhibited at the Fisheries and Maritime Museum. Photo: Port Esbjerg.

Go to overview