The size and capacity of wind turbines are constantly increasing, and the upcoming turbines are as tall as the Eiffel Tower. This poses special logistical challenges when transporting the rotor blades and towers measuring more than 100 metres to and around the port. However, this challenge can be solved, according to one expert, whereas another believes in more coastal manufacturing plants.

The Port of Esbjerg recently welcomed wind turbine blades with a length of 88.4 metres. They were transported by lorry all the way from Lunderskov. Meanwhile, nacelles weighing 390 tonnes are being sailed to the port. Other smaller nacelle components are driven to the port and assembled. The wind turbine towers of 100 metres are lined up on the quayside after being assembled from the tower sections of 30 metres or so, which arrived to the port by motorway. In other words, the port has adapted to accommodate the huge growth in wind turbines over the past couple of years. A growth that has been rapid.

Three-metre tall turbines

In 1976, a 19-year-old man spent his spare time building a wind turbine on his parents' farm in Jutland. The name of this enterprising young man was Henrik Stiesdal, and he went on to become a pioneer of the wind turbine industry. However, no one knew that back when he was mounting his wind turbine on a tractor trailer. That wind turbine was about three metres tall. 42 years later, the wind turbine industry has exploded in size as have the turbines. Blade manufacturer LM Wind Power is currently producing blades for turbines that measure 260 metres from top to bottom, with a rotor diameter of 220 metres and blades of 107 metres each. On drawings of the turbine, it is compared to the Eiffel Tower. Put one of the blades on a football pitch and it would extend over the goal line.

Constantly pushing the limit

"We have often been surprised by the size after pushing the limits," says Jesper Månsson. He is Chief Technology Advisor at the rotor blade manufacturer LM Wind Power, which is the world's largest producer of wind turbine blades. Jesper Månsson has worked with rotor blades since 1990, and he does not see the growth in size and capacity stopping any time soon. "I had actually thought we would see a pause after we launched our 88-metre rotor blades but that didn't happen," he explains. Jesper Månsson has helped push the limits of what is possible a number of times. "When we launched our 61.5-metre blades for a 126-metre-diameter offshore turbine back in 2004, people thought – wow, they're big. How much bigger can they get? But it just continued," says Jesper Månsson. The new turbines will supply 12 MW. By comparison, Henrik Stiesdal's first turbine produced 2-3 KW when the wind was blowing hard. The new turbines supply a good 4 million times more electricity than Henrik Stiesdal's homemade turbine on the tractor trailer.

Young industry

There was no wind turbine industry in 1976, but Vestas displayed interest in Henrik Stiesdal's wind turbine, and after some years of collaborating with Vestas, Henrik Stiesdal joined Bonus Energy, which was subsequently acquired by Siemens. He spent a total of 28 years leading the wind turbine company. According to Henrik Stiesdal, the industry accelerated from the mid-1980s. The turbines did the same. From 1989-2001, Bonus was growing at a rate of 40 per cent every year, and the turbines were doubling their capacity every four years. An exponential growth.

In 1991, the world's first offshore wind farm was built on Lolland. It was so far-sighted that it was nine years until the next was built near Middelgrunden close to Copenhagen, which has 2 MW turbines with a hub height of 64 metres and a blade length of 37 metres. But from then on, the pace picked up. Construction work continued in the UK and Sweden, and by about 2004, activity levels abroad matched those in Denmark. "However, looking back, that means the offshore turbine industry's track record with large volumes actually only spans about 15 years," says Henrik Stiesdal. That is why the industry is still developing significantly. And consequently, there is still a wide spectrum of challenges.

Rough waters ahead

As a supplier, competition is fierce and the pace of developments is high, accompanied by the constant need to match other companies. At the same time, there are technical risks associated with erecting relatively new offshore turbines. It entails the risk of so-called serial damages. Meanwhile, over the past 15 years, foundations and transport vessels have had to be developed because the ships were typically previously used for oil and gas. "They are not always geared for serial production. There is huge potential in industrialisation," says Henrik Stiesdal, citing the Port of Esbjerg as an example of what can be gained by systematising the category. "The Port of Esbjerg has it under control. But working 50 kilometres out in the North Sea is still difficult," he says.

Where will it end?

In recent years, there have been discussions in the sector about how big the turbines will become, and how they will be built and transported. According to Henrik Stiesdal, two contradicting trends are taking place. The turbines become more expensive in terms of the amount they produce when they are larger. According to the Square-Cube Law, which describes the ratio between volume and surface area, the weight increases significantly when the size of the shape is increased. If you double everything on a turbine with a rotor diameter of 164 to 324 in diameter, the wingspan of the turbine will be four times larger. However, it will be eight times heavier. This makes the turbine much heavier per kilowatt than before. "It is also this law that means birds cannot grow bigger than 20 kilos because they'll be too heavy to fly," says Henrik Stiesdal. Therefore large turbines are generally less competitive than small ones.

On the other hand, large turbines make the infrastructure cheaper. A foundation for a 3 MW turbine costs largely the same as a larger foundation, and means that there are fewer foundations to service. Meanwhile, the blade design has become refined and the material improved, explains Jesper Månsson from LM Wind Power. "Through a combination of technological improvements, we have succeeded in reducing the scaling factors," says Jesper Månsson. To date, the improvements have compensated for the more expensive and heavier turbines. "But at some point the party will stop," says Henrik Stiesdal. Because the ships are large and expensive, and the number of turbines is low, it means that the production will not be industrialised.

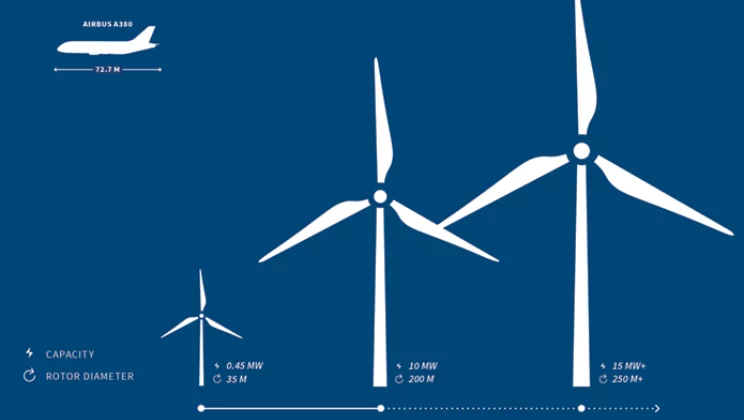

But is there an upper limit for when the turbines will be too large? Based on current trends, the limit is at least higher than where we are today. Today, there are 10 MW turbines. GE is launching a 12 MW turbine. And the national test centre for wind turbines in Østerild is prepared for turbines of up to 330 metres in height. "It's very likely that 15 MW turbines will be available in the first half of the 20's. But will they be competitive? We don't know yet," says Henrik Stiesdal. Jesper Månsson believes that the blades can be considerably larger. "Could we see a rotor diameter of 250 metres? Yes, we could," he says. "But at some point, some lines will begin to cross each other. We just don't know when," says Jesper Månsson.

Will production be based at the port?

According to Henrik Stiesdal, the industry is debating whether the growth in turbine size will also mean that they will have to be produced at the ports. Siemens Gamesa has built a manufacturing facility in Cuxhaven, Germany. However, at the same time, a good half of the world's offshore turbine towers are made by Welcon in Give, Denmark. "The town of Give is 70 km from the coast. You can hardly get further away from the sea at any point in Denmark," says Henrik Stiesdal. He highlights that today, towers with a diameter of 6-7 metres are driven from Give to Esbjerg and there are plans over the next few years to transport sections measuring 8-10 metres. "It is possible. Some suppliers might be located at the ports, but it is not a problem transporting towers by road.

"25 years ago, there was a big fuss about a tower measuring 32 metres being transported by road, but today a 75-metre long blade is transported to Lolland for a paint job without any problem," says Henrik Stiesdal. Jesper Månsson from LM Wind Power has a different view and does not entirely agree. According to him, the offshore elements, at least the rotor blades, with both large rod diameters and lengths, are now so big that it is difficult to transport them over land. "It seems as if being based near the coast may be necessary in the future. Blades of 107 metres have a rod diameter that can't fit under a motorway bridge. So when we reach that scale, we need to be at the coast," he says. For that reason, blades of 107 metres are produced in Cherbourg, France, at a factory near the coast.

Although LM Wind Power has also exported a number of onshore rotor blades from its manufacturing facilities in China, Jesper Månsson thinks it will be necessary to produce the very large blades near their markets, which would require a constant and stable market, however, if the investment is to pay off. "Blades will also be moved around the world, but many will be produced in close proximity," he says. USA’s only functioning offshore wind farm, Block Island, has rotor blades that were produced in Spain. "However, it brings down the logistics costs if you are near the port," he says, mentioning a range of challenges like those posed by the large blades. "Transport permits are becoming harder to obtain. Trees have to be cut down. Roundabouts must be expanded and that kind of thing." However, he is not completely uninclined to agree with Henrik Stiesdal. "During all the years, when we've been concerned about size, we've been asking ourselves how we will manage to move the components around. And we've always managed. So Henrik Stiesdal has a point,” says Jesper Månsson.

Henrik Stiesdal and Jesper Månsson.

Changing role for the port?

According to Henrik Stiesdal, the port's role in the future will not change significantly even though the turbines are changing. The same applies, even though the market is slowly moving to other locations than the North Sea. There will be plenty of wind power activity in Esbjerg, even if towers are perhaps built locally. "Things are happening in the Mediterranean, USA, China and throughout the rest of Asia. The total volume will increase. That's why the pressure will not decrease," he says.

Henrik Stiesdal believes conditions in the North Sea are good enough for the offshore wind power projects to continue. "After all, the North Sea is an anomaly. There are very large areas with shallow water close to densely populated centres with many hundreds of millions of people living a realistic distance from the production, and where there is plenty of wind. So regardless of the size of the turbines, the North Sea is central for offshore wind power worldwide, and there will be many projects in the future and lots to do at the ports," he says. The Port of Esbjerg is also ready for the further developments. "We are adapting access roads and roundabouts. We can handle the large turbines," says CCO Jesper Bank. But Jesper Bank also points out that preparations are being made for manufacturing facilities coming to the ports.

Go to overview